How Google selects the victor in an ad auction was elucidated by Dr. Adam Juda, Vice President of Product Management in Search Ads Quality Systems, during the federal antitrust trial:

- The ad auction’s winner is not solely determined by the highest bidder.

- Rather, greater emphasis is placed on a campaign’s long-term value (LTV).

- This approach occasionally results in Google sacrificing short-term financial gains.

When advertisers participate in keyword bidding, Google doesn’t rely solely on bid amounts to determine the ad auction winner.

Instead, Google utilizes a metric known as Ad Rank to determine the ranking and eligibility of a campaign.

This comprehensive score is derived by assessing:

- Bid amount

- Auction-time ad quality (including expected click-through rate, ad relevance and landing page experience)

- Ad Rank threshold

- Competitiveness of an auction

- Context of a search query

- Expected impact of assets and other ad formats

Your Ad Rank is recalculated every time time your campaign becomes eligible to compete in an auction, meaning your ad’s ranking may vary each time depending on competition, quality and search context.

Campaigns that don’t meet Google’s minimum Ad Rank threshold are automatically eliminated from the auction

How does Ad Rank work?

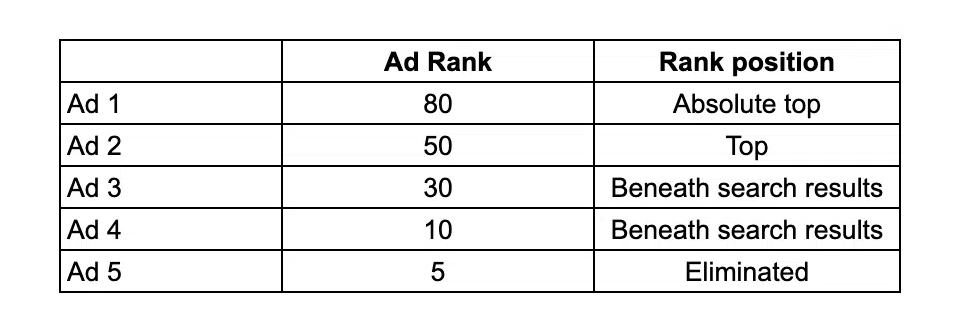

Imagine five advertisers competing against each other in an ad auction with respective Ad Rank scores of 80, 50, 30, 10 and 5. For this particular auction, Google requires a minimum Ad Rank threshold of 40 to rank above organic search results. This means that only the first two campaigns (with scores of 80 and 50) are eligible to show above organic search results.

In this instance, for an ad to be shown below organic search results, Google requires a minimum Ad Rank of 8. This means that campaigns with Ad Rank scores of 30 and 10 would qualify.

However, the campaign with the Ad Rank score of 5 does not meet the minimum criteria to appear above or beneath the search results, and so will be eliminated from the auction, as shown in the table below:

So why doesn’t the highest bidder win?

If the highest bidder automatically won every Google ad auction, there is a risk the search engine could be left serving poor-quality ads. Poor-quality ads may not be relevant to a searcher’s query, which would likely result in a poor:

- Click-through rate.

- Conversion rate.

- User experience.

This would decrease the overall value of Google’s product.

An ad that meets all minimum criteria required by a Google auction can sometimes still rank below an ad that fails some criteria, he wrote.

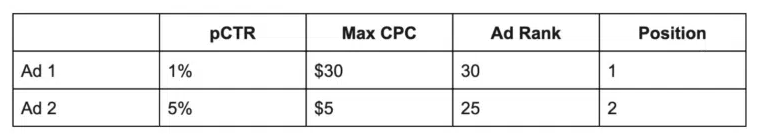

Vallaeys went further by using an example of an ad auction that had a 4% threshold for predicted CTR. The details of the competing bids are listed in the table below:

In the given example, Ad 2 qualifies as it surpasses the threshold with a predicted CTR of 5%, which is 1% higher than the 4% requirement set by Google. Nevertheless, due to Ad 1 having a superior Ad Rank score of 30, Ad 2 would be positioned lower on the page to maintain auction fidelity, only appearing when Ad 1 is permitted.

Acknowledging that this situation is suboptimal for both advertisers and Google, they address it by permitting ads to appear in an order different from what the ad rank would typically dictate. This divergence is encapsulated by the concept of RGSP.

What is RGSP and how does it affect auctions?

RGSP is a practice leveraged by Google that picks the winner of an ad auction at random from the top bidders as long as their long-term values (LTVs – a Google calculation that is essentially the same as Ad rank) are close enough.

The top bidder then “pays the price of the bid equal to the next-highest bid plus one cent,” according to Big Tech on Trial.

The Department of Justice argued at the federal antitrust trial that this practice creates an unfair competition for bidding advertisers as the winner of an auction should always be the highest bidder.

Why is RGSP unfair?

Advertisers have two options if they want to avoid their potential winning bid from being demoted at random to runner-up:

- Improve their campaign’s LTV.

- Increase their bid amount.

The issue here is that Google hasn’t specified exactly how advertisers can increase their campaign’s LTV, which leaves them with one option if they wish to avoid RGSP – increase their bid amount.

To avoid RGSP, the bid amount would have to be significantly higher than the runner-up (as mentioned before, winners and runners-up can only be swapped via the RGSP process if the LTV and bid amounts are close enough). This has resulted in advertisers having to raise their bid 3.7 times higher, reports This Week In Google Antitrust.

What are the issues with RGSP?

Jay Friedman, CEO of advertising agency Goodway Group, highlighted the reasons RGSP could prove problematic for advertisers:

- “Imagine you want to buy a ticket to a concert. Not everyone who wants a ticket can get a ticket, so there is an auction. You submit your bid and it’s not a first-price auction (highest bidder wins, pays what they bid) and not even a second-price auction (highest bidder wins, pays a nominal amount [i.e. $1] over the second-highest biddger.) Instead, the concert venue holds an RGSP – a ‘randomized general second-price auction.’”

- “Let’s say the the top two bidders submit bids of $100 and $95. In RGSP, the concert venue takes the top two bidders and, ‘as long as the long-term value of each of the bidders to the concert venue is pretty close,’ there is a chance the concert venue randomly swaps the top two bidders and awards the seat to the second highest bidder instead. Sounds like a deal if you randomly get the ticket for $95, and I guess frustrating for the highest bidder.”

- “EXCEPT – the concert venue tells you there are two ways to make sure you don’t get randomly swapped out as the highest bidder. One, increase your long-term value to the venue. They don’t tell you how to do this and note it may include your behavior, referrals, bid amounts, bid frequency, ‘and other bidder quality elements.’ You decide that’s pretty vague. The second is to increase your bid! And, as it turns out, you’d have to increase your $100 bid to $370 to get sufficient confidence you wouldn’t be outbid.”

While out-of-order promotion changes the typical auction dynamics, Google believes it ultimately improves the search experience, and I tend to agree with that. For advertisers, it highlights the need to focus both on bidding strategically and optimizing for relevance and Quality Score.”